By Chris Campion

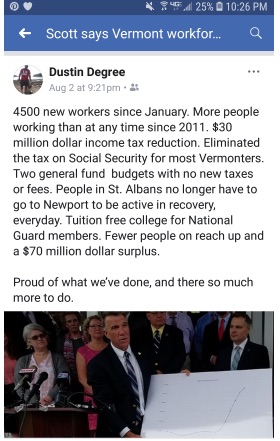

Dustin Degree, former member of the Vermont Senate, and now member of the Scott administration as executive director of workforce expansion, recently posted on Facebook some encouraging employment and workforce data.

What he posted is good news, but much like Peter Shumlin, former governor of Vermont’s routinely rosy employment proclamations, what lies underneath the data is what’s relevant and needs a closer look.

What he posted is good news, but much like Peter Shumlin, former governor of Vermont’s routinely rosy employment proclamations, what lies underneath the data is what’s relevant and needs a closer look.

“4,500 new workers since January”

This type of information always needs to be viewed in context, and the timing of the start and end dates of the comparison is interesting. Rarely are the types of jobs gained mentioned in these numbers, too, as it could be 4,500 new workers flipping burgers. While burgers need flipping, 4,500 new burger-flipping jobs won’t raise median incomes in Vermont, nor provide someone the ability to buy a home in a state where the home prices are catastrophically high.

In looking at the Vermont Department of Labor data (seasonally adjusted), the difference between January and June 2018 is 1,600 employees. Dustin might have access to updated data, but this is what the state officially publishes.

Secondly, of the total private sector gains in that period, almost half of those gains were in the Leisure and Hospitality industry — 800 of of the 1,800 fell into this category. So, close to 50 percent of the job gains were in an industry where the incomes are at the lower end of the spectrum.

To be fair, there were gains in Financial Activities (400) and Professional and Business Services (900), but many of those positive gains were offset by losses in Manufacturing, Trade Transportation and Utilities, and other categories. In fact, the total losses in Manufacturing and Trade Transportation and Utilities was 800 — which completely negates the gains in the Leisure and Hospitality sector.

“More people working at any time since 2011”

More people working is always good news, but why pick 2011 as a start date? The state’s employment data goes back to 1976. 2011 isn’t in the top 10 of overall employment years. 2011’s average employment number was 338,443. The 2006 average is 343,830. Which means, 10-plus years ago, we had 5,000 more people employed in Vermont than we do right now. In fact, the average employment number from 2011 to 2017 is 334,891 – which is pretty close to January 2018’s employment number of 335,233.

Which looks to me like there hasn’t been much improvement in overall employment in the last decade. If we have to go back to the salad days of 2006 for higher employment numbers, which Degree ignores to make comparisons more favorable, then he’s missing the point. Vermont is still regressing, from an employment point of view.

Oh, and if you need more data on this, Vermont’s incomes are only at 80 percent of the regional income level (New England). Meaning Vermont’s still behind everyone else in New England, in terms of incomes, and has been that way for the past three decades, as Art Woolf details below:

“Vermont lost ground against our neighbors during the late 1970s but for the last three decades it’s been stable at about 80 percent of the New England average. We are an above-income state compared to the nation, but we are (sic) still the poor cousins in a rich region. Connecticut and Massachusetts have the highest per capita incomes in the nation and New Hampshire ranks seventh. At nineteenth highest, Vermont has a long way to go to catch up, and we’re unlikely to see that happen. Ever.”

“Two general fund budgets with no new taxes or fees”

Lastly, although this has little to do with employment specifically, the elephant in the room that always goes purposefully unnoticed is the state’s unfunded liabilities exposure, which is now in the billions:

Unfunded obligations in the teachers’ pension program, which was less than $400 million in 2008, had grown to $1.5 billion by 2017. For state employees, the unfunded portion of the pension program increased from $87 million in 2008 to $717 million in 2017.

So, while no new taxes or fees is a good thing in the short run, in the long run the state is ignoring its responsibility to fund the pensions it owes, largely to the state’s teachers.

But Scott isn’t alone in addressing the this last looming issue, as prior governors have been kicking this pension bomb down the road, and there will likely have to be some kind of national reckoning on it. Which means more taxes and more debt to pay off promises made but never kept by politicians at the state and local level, because it never hurts to promise something to someone when someone else has to pick up the tab.

Maybe this means Scott, and Dustin Degree, can celebrate the above gains a little less loudly. Decades of negative economic policies will take years to unwind, and a lot of work to undo what’s been done to Vermont.

It’s a start. But it’s only the beginning, and the bulk of the work lies in front of Gov. Scott and Dustin Degree.

Chris Campion is a business analyst who worked for decades in leading organizations in Vermont. Reprinted with permission from the Ethan Allen Institute Blog.

Pay day some day and sooner than you think.

Continuing the no new taxes approach without actually cutting waste is going to come back and bite us. The democrat approach to raising taxes if neither party is going to cut spending is unfortunately the right approach because there will be no major problem down the road.

This is not endorsing the democrats because both theirs’ and the governor’s approaches is destined to fail. I keep hearing from people saying we can’t afford Hallquist because the taxes will go up drastically. Either way we will be feeling the pain whether it’s sooner or later.