Editor’s note: This article by Bruce Parker originally published Sept. 16, 2016, on Watchdog.org.

Vermont’s secretary of state says the election system is secure after hackers breached databases in Arizona and Illinois, but the ballot-counting machine at the center of the state’s voting process offers little reason for confidence.

Is Vermont’s election secure? The answer may come down to the optical scanners being prepared for use in hundreds of towns and polling places across the Green Mountain State.

Since the FBI informed state officials last month that foreign hackers compromised multiple state Board of Election systems, election chiefs in all 50 states have been working overtime to keep their voting systems protected from a hostile cyber attack.

On Aug. 31, Secretary of State Jim Condos announced that his staff found “no abnormal activity” as described in the FBI’s alert. He further said his office has “taken precautionary steps to safeguard our elections systems,” most notably data systems and the statewide voter checklist.

But FBI officials are preparing to announce more states whose systems were hacked, according to CBS News, and Homeland Security reportedly will provide detailed preventive measures to secure election systems.

The flurry of activity has Condos worried.

“We really take this seriously. I think it’s important for Vermont voters to know that we are really well prepared and that we are taking precautionary steps to safeguard our election systems,” Condos told Watchdog in an interview Tuesday.

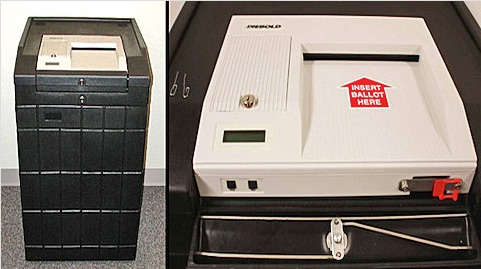

HACKABLE: Vermont’s voting system is based on an optical scanning machine that has a reputation for being easy to hack.

For most Vermont towns, digital security comes down to a ballot-counting optical scanner known as the AccuVote-OS. The unit, formerly made by Premier/Diebold, is now owned by Dominion Voting Systems.

In polling places across the state, Vermonters mark in ovals on paper ballots and feed them into the AccuVote-OS, which captures the vote in its memory card. The paper ballots drop into a storage box, where they are kept on hand in case of a contested election.

The machine’s all-important memory cards are managed by LHS Associates, of Salem, N.H. The company maintains custody over AccuVote-OS memory cards for all machines across New England.

“The machines we use are EAC certified. In fact, they have one of the highest certification levels from the Election Assistance Commission,” Condos said.

For anyone who has seen the AccuVote-OS hacked in various demonstrations over the past decade, such certifications offer little comfort. Security experts have demonstrated repeatedly that AccuVote-OS is shockingly easy to reprogram, and that the only way to verify its tallies is to conduct a hand-counted audit of the paper ballots.

In one demonstration by Princeton University computer science professor Edward Felten, a mock election between George Washington and Benedict Arnold doesn’t go well. While Washington gets three paper ballot votes and Arnold gets none, the optical scanning machine gives the infamous traitor a 2-1 victory. Malicious computer code surreptitiously added to the machine’s memory card switched the votes, and no one could have suspected it.

Hacking Democracy

In the the Emmy nominated HBO documentary “Hacking Democracy,” election specialists watch in stunned amazement as paper ballot votes fed into the optical scanner are reported incorrectly on the machine’s paper spool printout.

As seen in the video, Florida Leon County Supervisor of Elections Ion Sancho, along with five other individuals, vote “no” on a single ballot question, while two others vote “yes” — a 6-2 no vote on paper. What happens next is disturbing.

The elections supervisor inserts the AccuVote-OS’s detachable memory card into the slot, runs a “zero-total test tape” at the machine’s startup to show zero votes on the memory card, and inserts the eight paper ballots into the optical scanner. The result of the election according to the AccuVote-OS machine? A 7-1 yes vote, to the dismay of the observers. One woman breaks down in tears.

“If I had not seen what was behind this … I would have certified this election as a true and accurate result of a vote,” the elections supervisor says in the scene.

The machine not only switched the vote on the paper spool print-out, but on the memory card itself. The hack is known is cybersecurity circles as “the Hursti Hack,” named after the security expert who carried out the demonstration.

While the documentary was filmed in 2006, Felten, along with fellow Princeton professor Andrew Appel, told Politico last month that little has changed for digital vote-counting machines, and that stealing an election takes just seven minutes.

Condos, not a cybersecurity expert, nevertheless expressed confidence that the AccuVote machines are secure.

“Any of the videos that you probably looked at are old videos, from the standpoint of that was on a previous version of the memory card. The newer chips — and that’s what we have in Vermont — address many, if not all, of the issues that were raised at the time,” he said. “Secondly, there is a chain of custody here. That’s the important piece. There is a chain of custody, and the chips come from the vendor who programs the chips but then gets them directly to the clerks.”

Town clerks are instructed to keep the memory cards “in their vaults under lock and key,” Condos said, and LHS Associates sends the cards less than four weeks out from the election “so they don’t get them way early.”

That means memory card tampering is unlikely to occur from election officials at polling places. But who monitors the third-party custodian of the all-important memory cards, LHS Associates?

“I can’t tell you if there’s someone from the federal government that goes in and checks it — I don’t know that,” Condos said. “But I know this LHS deals with, I think, pretty much all of New England using the same kind of machine.”

Why digital voting machines

According to Verified Voting, a non-partisan organization that promotes election transparency and verifiability, about 135 towns in Vermont use the AccuVote-OS optical scanner. Another 110 Vermont towns count paper ballots entirely by hand.

The digital tabulators became popular following the 2000 Bush-Gore election recount, when the “hanging chad” debacle of Florida’s manual punch-cards led Congress to pass the Help America Vote Act in 2002. Lawmakers appropriated $4 billion for all 50 states to upgrade systems to computerized voting machines.

Some states updated to paperless touch screen systems known as DREs, or direct recording electronic systems. Those machines are increasingly criticized because they leave no paper trail.

Five states — South Carolina, Delaware, Georgia, New Jersey and Louisiana — use DREs statewide without any paper trail. The swing states of Florida, Texas, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Tennessee and Indiana use DREs without paper trails in some locations.

But in Vermont, a paper ballot counted by an optical scanner allows for an audit of the vote tallies reported by the AccuVote-OS machines. Verification would require hand-counting paper ballots and comparing the results to tallies produced by the digital scanners.

Condos didn’t say if his office compares numbers reported by AccuVote-OS machines with a hand count of paper ballots, but he did mention an audit.

“Within 30 days of the general election we do a random audit where we are checking the entire election for that town, from president on down to justices of the peace. We do an audit to check the numbers of the audit versus the numbers of election night. We have several steps that we do, and we’re really confident our system is in pretty good shape.”

He stressed that the machines are not networked together, or to the Internet, making it impossible for an Internet-based hacker to infect all the machines at once using a programming virus. Only LHS has such access, through its custody of the memory cards sent to, and retrieved from, town clerks.

“For someone to go in to hack it they would have to break into a town clerk’s office, steal the chip, hack into it, put the chip back, and have it used,” Condos said.

Condos recognized the importance of a paper trail and said he was instrumental in keeping it in Vermont.

“Vermont was one of the leaders on this back in 2002, post Florida, and during the HAVA discussions,” he said. “We at that time put into statute — in fact, I was on the committee, and I think I made the motion — to require that there be a paper ballot at the end of the day. So, we always have the paper trail at the end of the day.”

In the documentary, Sanchos concludes that hand-counting paper ballots is necessary to audit the AccuVote-OS machines. He also said it’s necessary to keep a watch on the vendors who control the memory cards.

“I think we, as election officials, need to be a little bit more demanding from the vendors as to the technical specifications of this equipment. The vendors are driving the process of voting technology in the United States. I would much rather at this point, I think, focus on allowing citizens to select technology that satisfies their needs.”

Condos, Vermont’s chief elections officer, reiterated that he believes his machines are safe.

“We purchased new machines this past year as we increased the number of towns and have not had any problems with them,” he said. “I’ve only been in office since 2011, but I was in the Legislature prior to that for eight years, and on the committee that oversaw the Secretary of State’s Office. To my knowledge, we’ve never had a problem.”