By Nick Storz and John Schoof | The Daily Signal

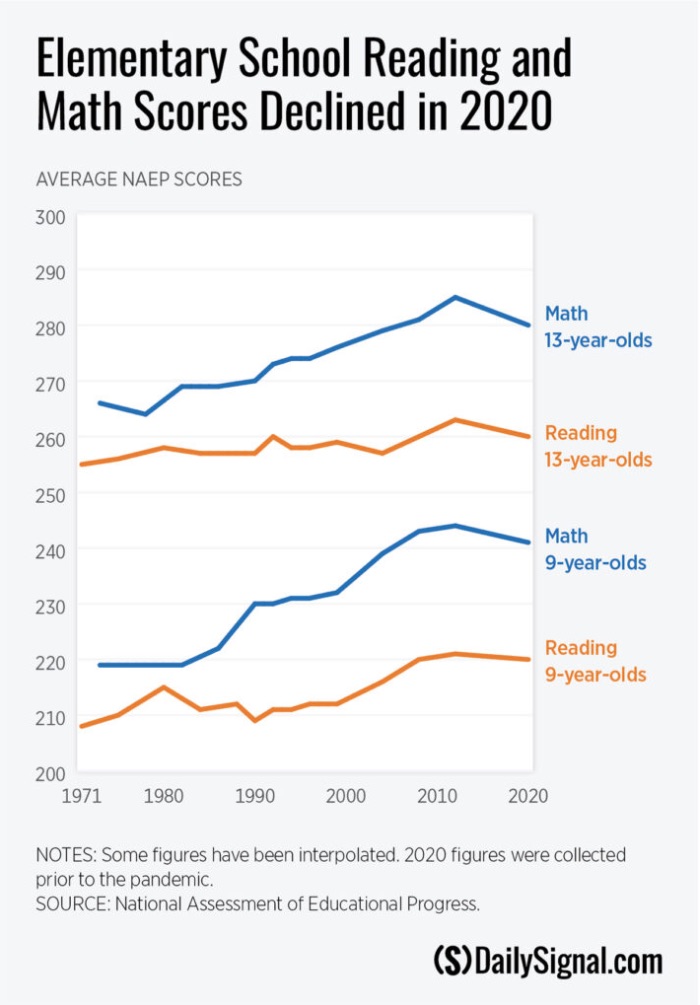

For the first time in the study’s 50-year history, the National Assessment of Educational Progress’ 2020 Long-Term Trend Assessment revealed that U.S. 13-year-olds’ scores in both reading and math experienced statistically significant declines over the past eight years.

Despite record-high education spending, these declines are the latest evidence casting significant doubt on Common Core’s learning standards and approach to student improvement.

Reversing a 2 decadelong trend of score improvement, 9-year-olds’ test scores saw no change since the test was last administered in 2012.Meanwhile, 13-year-olds’ scores in reading fell by three points.The steepest declines by far, however, were in 13-year-olds’ math scores. Overall, they declined by five points.

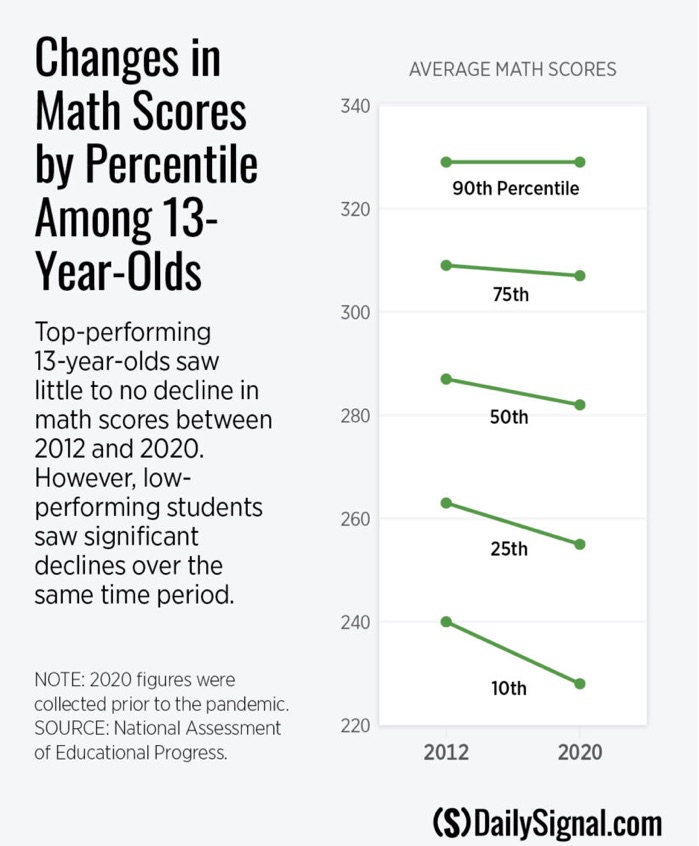

For minority students, the drop was even worse, with black students’ scores falling eight points, while Hispanic students’ decreased by four, widening achievement gaps.Students scoring in lower testing percentiles experienced the most distressing declines. The math score of the median student dropped by five points, the 25th percentile fell by eight points, and the 10th percentile fell by a shocking 12 points.Considering a 10-point change is considered to represent a grade level, 13-year-old students scoring in the 10th percentile dropped more than the equivalent of a full grade year in math capabilities below where they were in 2012. Black students and students in the 25th percentile were close behind.

Changes in NAEP scores by age, race and subjects

The stark declines are especially worrisome given the assessment took place before COVID-19 struck, meaning they omit pandemic-induced learning loss.Researchers also expected improvement during the eight-year span. The decrease in math scores, an area that historically experienced comparatively higher gains in scores than reading, is especially disheartening.Pundits offer competing explanations for the downturn. Many argue the declines are the long-term effects of financial hardship and cuts in state education spending during the Great Recession. They claim it disrupted skills formation for children now in their teens.

While overall per-pupil spending decreased from 2008 to 2013, it fell by only $631 (about 4%), thanks to increased federal spending. For context, per-pupil spending has increased 39% since 1990, nearly tripled since 1966, and has hit record highs every year since 2016 (during which now-13-year-olds would have been learning the skills tested on the most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress).

Meanwhile, the vast majority of the research literature doubts the strength of the relationship between school resources and student achievement.

An alternative and worrisome correlation is the introduction of Common Core Standards. Released in 2010 and implemented between 2013 and 2015, Common Core Standards are a collection of curriculum and teacher standards, including a national list of topics students should learn in each grade to be considered “college-and-career ready.”

Researchers point to fundamental flaws in the Common Core Standards’ approach to mathematics learning and content coverage as correlating to negative trends in student learning.

First, the Common Core Standards focus heavily on imparting a conceptual understanding of math to the detriment of building computational skills. Common Core Standards advocates argued that simple computational tricks like “Parentheses, Exponents, Multiplication/Division, Addition/Subtraction” or crossing off zeros when dividing don’t teach any math concepts, leading students to approach tests with a “grab bag of tricks,” rather than thinking about questions.

Sidelining practical skills in favor of conceptual learning may have gone too far. Many parents seem to agree, worrying that Common Core Standards have led teachers to throw out proven practical methods in favor of convoluted solutions.

Speaking to the website The74 Million.org, Tom Loveless, former director of the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brooking Institution, concurred, noting: “Without computational skills to anchor math concepts, students get lost.”

That could explain eighth graders’ poor performance on the Long-Term Trend Assessment, which features more basic math problems, emulating the way the subject was taught in the 1970s.

Moreover, Common Core curriculum content standards have significant gaps that leave students poorly prepared. Common Core Standards math pushes Algebra I from eighth grade to high school, contradicting a discipline-wide consensus.

Instead, studies from California show the number of eighth graders enrolled in Algebra I precipitously declining after adoption of Common Core Standards. Reduced exposure to variables and other Algebra I concepts present on the Long-Term Trend Assessment could also help explain eighth graders’ lower performance.

Moreover, a report from ACT suggested many teachers in early elementary school and in fourth-seventh grade report feeling the need to teach math topics Common Core Standards omitted, or teach topics earlier than the standards recommend.

While some teachers may go above and beyond to fill those gaps, teachers adhering to the Common Core Standards may inadvertently be leaving 13-year-olds underprepared for the Long-Term Trend Assessment.

Whenever disappointing results emerge in education, the predictable and politically expedient answer is to point to a “failure to invest” in education.

In an era where the United States boasts the highest per-pupil spending in the nation’s history and of all major developed countries in the world (even when excluding COVID-19 relief spending), that excuse is no longer an option.

Rather, these disturbing scores warrant a meticulous and honest reevaluation of the fundamental incentives and standards in our education system.

An excellent place for policymakers to start would be to dismantle Common Core math standards, allowing states to replace those standards with research-tested academic benchmarks proven to prepare students for college academics.

For blueprints, states can look to rigorous math standards adopted by Massachusetts, California, or Illinois pre-2010.

While a smoking-gun study directly linking Common Core Standards to math score declines has yet to be conducted, the available evidence strongly suggests those standards no longer deserve parents’ confidence.

Meanwhile, concerns are mounting among researchers that the standards drag down American students’ academic achievement below that of their international peers, while threatening to reverse a decade of scholastic gains.

Blaming poor student academic performance on Common Core (CC) is a myopic and misleading misperception. The few states that didn’t implement CC saw similar declines in academic performance. After all, CC is only the most recent, and obvious, permutation of the pedagogic dysfunction infesting our public education system for the last 50 years.

Parents, and society in general, are now focused on education because of recent epiphanies exposed by ‘remote learning’, their realization of what class plans really are, and the education establishment’s heavy-handed attack on them as the new ‘domestic terrorists’ when they at first inquire, and then protest.

The problem is, of course, that the public education system is a monopoly. One size fits all. The Teacher Unions, Principal and Superintendent Associations, and, especially, the special interest conflicted school boards, are a party to this diversion criticizing CC.

Today it’s Common Core. In the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s it was Whole Language, New Math, and, later still, the demise of individual, merit-based recognition – all implemented with devastating consequences for years. When everyone gets a trophy, there is no accountability. When accountability vanishes, so too does the incentive to excel. Is it any wonder academic performance is declining – by virtually every measure and with every change in curricula?

Don’t fall for this diversion away from the true systemic problem. It’s educational ‘pillow arranging’. Just eliminate the public-school monopoly by allowing parents to choose the education programs they believe best meet the needs of their children – especially now – while they are finally paying attention.

One of the most interesting things about this article is that the test scores shown are incomprehensible to so many. Why can’t the educational establishment grade all kids on a 0-100 score like they used to so everybody knows how the kids are doing? Oh…you mean…they don’t want us to know?