Editor’s note: This article is by Lou Varricchio, editor of the Sun. It is republished here with permission.

In popular accounts of the U.S. Civil War, you won’t across many, if any, references to U.S. Army Brig. Gen. Edward Hastings Ripley.

The Rutland-born general attained the rank at age 25, and along with Gen. George Armstrong Custer, was among the nation’s youngest generals ever appointed in the War Between the States.

In 1862, Ripley responded to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 300,000 fresh volunteers to fight in the nation’s bloodiest-ever civil uprising. Ripley doggedly recruited soldiers from Rutland, Bennington, and Addison counties (among others) under the banner of the Ninth Vermont Volunteers, and became captain to these men when they trained to the southern front of the war.

Ripley was born in downtown Rutland in 1839. His father, William Young Ripley, owned a large estate in the city known as The Center and was founder of the Rutland County National Bank and Ripley Sons, a local industrial marble company (later sold to Redfield Proctor’s Vermont Marble Co.).

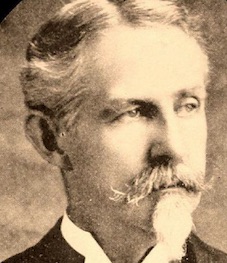

Gen. Edward Hastings Ripley, Rutland

In those days, Ripley’s estate was located within the city of Rutland, but later redistricting created Rutland Center, Rutland Town, and West Rutland. The Center stood in what is now Rutland Center.

General Ripley’s older brother William Y.W. Ripley, joined the Army as a caption, too, during the opening months of the war. William was the first of the Vermont volunteers to head to war under the banner of the Rutland Lightguard, the state’s first responders. Young Edward, a medical student at Union College in New York in 1861, couldn’t wait to join up despite his mother’s protest.

Finally, Mrs. Ripley relented (with the gentle urging of her husband) and the couple supported their son Edward’s call-to-action even after their oldest son was badly wounded at the Battle of Malvern Hill in Virginia.

Between his enlistment in 1862 and his discharge at war’s end in 1865, General Ripley narrowly escaped death on several occasions. After the surrender of Harper’s Ferry, Ripley battled internal demons while a paroled prisoner returned to the North at the Union’s Camp Douglas in Illinois. Oddly, Confederates couldn’t handle their Yankee prisoners at Harper’s Ferry and thus paroled their Yankees POWs to the Union as part of a prisoner exchange with federal troops.

Despite the Harper’s Ferry debacle, Ripley was quick to gain valor and a brevet-general appointment. He soon saw fierce combat at the capture of Fort Harrison and at the repulse at Fort Gilmer. The Vermonter was also among the first Union officers to enter the defeated Confederacy stronghold of Richmond, Viriginia.

Ripley was a talented writer and because of it, today’s historians are the beneficiaries. His 400 detailed letters about daily life during the war-torn 1860s were sent from the Southern front to his family safe and snug in Rutland; the letters are rare gems among the annals of the Civil War. It’s too bad they aren’t being shared with a modern audience.

Sadly, General Ripley’s eloquent book of letters, published as “Vermont General: The Unusual War Experiences of Edward Hastings Ripley, 1862-65”, has not been in print since the Civil War Centennial. The classic book deserves new life with a new edition published and annotated for today’s readers.

Ripley lived a prosperous and contented life after the war. He served as a Vermont state representative (Republican) and continued in his father’s banking and marble business. He was a founder of the United States and Brazil Steamship Line, the New Jersey Raritan Railroad, and managed the building of the Holland House Hotel, located at 274–276 Fifth Avenue in New York City, in 1892. He died in Mendon, Vermont, in 1915, just prior to America’s entry in World War 1.

Tired of brother-against-brother carnage, many Vermonters at the time believed showy displays of patriotism would offend returning veterans. No so, said the general.

“Those who argue that henceforth the Fourth of July will be dull and stupid are wrong,” he wrote. “Salutues to our flag will stir the blood of thousands of men aching for noise and excitement, and it will thrill through them like wine to a thirsty man.”

No Ripley family member is alive in Rutland today, at least as far as The Sun can know. The Center, Ripley’s stately family homestead, became a clubhouse and later a private resience but you can still see it along old Route 4. General Ripley’s remains rest in hallowed ground beneath a stately monument in Rutland County’s Evergreen Cemetery.